The variety of CEN Study Guide available allows students to cover a wide range of topics and increase their knowledge base.

Obstetrical Emergencies CEN Study Guide

Placental Disorders

Pathophysiology

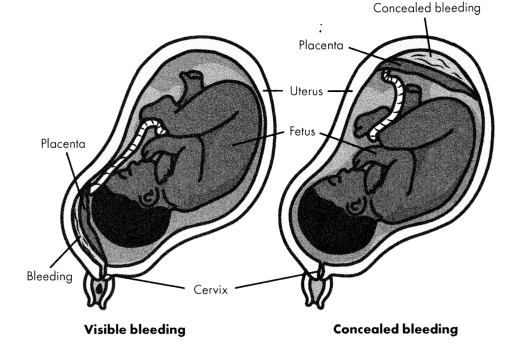

Abruptio placentae (placental abruption) occurs when the placenta separates from the uterus after the twentieth week of gestation but before delivery. Abruption can lead to life-threatening conditions, including hemorrhage and DIC. Blood loss due to abruption can be difficult to quantify as blood may accumulate behind the placenta (concealed abruption) rather than exiting through the vagina.

Figure 7.2. Abruptio Placentae

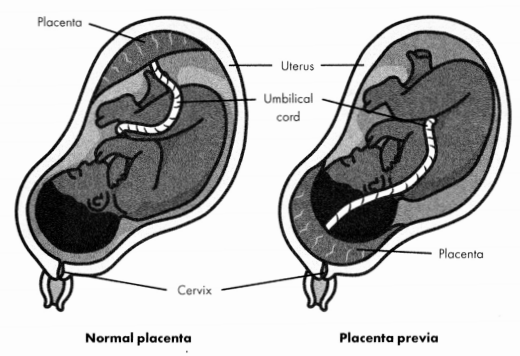

Placenta previa occurs when the placenta partially or completely covers the internal orifice of the cervix. A low lying placenta is located < 2 cm from the cervix but does not cover it. Placenta previa is usually asymptomatic and is found on routine prenatal ultrasounds. The presence of previa makes the placenta susceptible to rupture or hemorrhage and necessitates a cesarean delivery.

Placenta previa is correlated with placenta accreta, particularly in women who have had multiple previous cesarean deliveries. In placenta accreta, the placenta attaches abnormally deeply into the myometrium. Because the placenta cannot detach from the uterus after delivery, placenta accreta can lead to hemorrhage and requires a hysterectomy.

Figure 7.3. Placenta Previa

Risk Factors

- smoking

- cocaine use

- abruption:

- hypertension

- preeclampsia

- fetal abnormalities

- blunt trauma

- placenta previa:

- age > 35

- multifetal pregnancy

- previous cesarean delivery

- infertility treatment

Diagnosis

TABLE 7.1. Diagnosis of Abruptio Placentae and Placenta Previa

|

|

Abruptio Placentae |

Placenta Previa |

|

Onset of |

sudden and intense bleeding with pain |

asymptomatic or painless |

|

Bleeding |

bleeding may be vaginal or concealed |

vaginal bleeding |

|

Uterine Tone |

firm |

soft and relaxed |

|

Imaging |

transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound |

transabdominal or transvag¬ |

Management

- fetal heart sate monitoring

- monitor mother for signs of themodynamic instability

- RhoGAMifmother is Rh negative

- IV fluids or blood products as needed

- patient admitted stat to OB

Ectopic Pregnancy

Pathophysiology

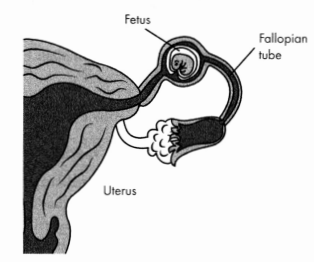

In an ectopic pregnancy, the blastocyst implants in a location other than the uterus. In > 95% of cases, implantation occurs in the fallopian tubes (tubal pregnancy), but implantation can also occur in the ovaries, cervix, or abdominal cavity. Ectopic pregnancies are most often caused by tubal irregularities that are congenital or the result of infection or surgery. A tubal pregnancy may rupture the fallopian tube, causing a life-threatening hemorrhage.

Figure 7.4. Ectopic Pregnancy (Tubal Pregnancy)

Risk Factors

- age > 35

- pelvic inflammatory disease

- STIs (chlamydia and gonorrhea)

- infertility or fertility treatments

- tubal surgery

- smoking

Physical Examination

- severe, unilateral pelvic vain

- vaginal bleeding

- lower abdominal pain

- s/s of hemorrhage

Diagnostic Tests

- pregnancy confirmation with urine or serum hCG

- transvaginal ultrasound to locate pregnancy

Management

- RhoGAM if mother is Rh negative

- hemodynamically unstable patients: stabilize and prepare for surgery

- hemodynamically stable patients: OB referral for surgery or treatment with methotrexate

Labor and Delivery

Pathophysiology

Labor and delivery occurs in 3 stages.

- Stage 1: onset of labor to full cervical dilation (12- 16 hours)

- Stage 2: cervical dilation to expulsion of fetus (2-3 hours)

- Stage 3: delivery of placenta (10- 12 minutes)

Delivery is imminent if the fetus is visible and/or the mother reports the urge to push with contractions. Alternatively, delivery can be considered the cervix is fully dilated (10 cm) and contractions are < 2 minutes apart.

Contractions and cervical dilation before the thirty-seventh week of gestation is preterm labor. If preterm labor begins between 34 and 37 weeks with no other complications, the patient should be transferred to the labor and delivery setting if delivery is not imminent. When preterm labor begins at < 34 weeks, the mother should be transferred to OB for treatment to delay delivery.

Risk Factors

- emergent delivery:

- unrecognized pregnancy

- unrecognized signs of labor

- lack of prenatal care

- trauma

- preterm labor:

- short cervical length

- infections (e.g., bacterial vaginosis, UTI, STIs)

- multifetal pregnancy

- underweight or obese mother

- diabetes

Physical Examination

- emergent delivery

- ruptured amniotic membrane (“water broke")

- urge to push

- dilation of cervix

- contractions

Diagnostic Tests

- pelvic exam: assess cervical dilation

- fetal Doppler to assess fetal heart rate

- transabdominal ultrasound: to identify presentation and number of fetus(es) and assess for possible complications.

Management

- Assess patient to determine stage of labor and gestational age.

- preterm labor or complications: OB consult stat

- delivery not imminent: patient should be transferred to OB for delivery

- delivery imminent and no complications: delivery will take place in the ED

- Monitor maternal blood pressure, heart rate, and contractions.

- Monitor fetal heart rate.

- Administer RhoGAM if mother is Rh negative.

- Administer betamethasone for imminent delivery of fetus < 34 weeks.

- Position mother is in lithotomy position for delivery.

- Clean perineum with antiseptic.

- Care of newborn postdelivery:

- Wipe nose and mouth; suction airway if obstructed.

- Dry and stimulate newborn.

- Assign Apgar score.

- Care of mother postdelivery:

- Deliver placenta.

- Administer oxytocin or perform fundal massage.

- Monitor for signs of hemorrhage.

Hemorrhage

Pathophysiology

Postpartum hemorrhage is bleeding that occurs any time after delivery up to 12 weeks postpartum and exceeds 1000 ml or that causes symptoms of hypovolemia. Primary hemorrhage occurs during the first 24 hours after delivery; secondary hemorrhage occurs between 24 hours and 12 weeks postpartum.

The etiology of hemorrhage varies.

- trauma: lacerations to uterus or vagina

- uterine atony: failure of the uterus to contract after delivery, often because of placental disorders

- subinvolution of the placental site: persistence of dilated arteries in placenta or uterus postpartum

- retained tissue

- coagulation disorders

- infection

Risk Factors

- placental disorders (accreta or previa)

- preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP

- failure to progress in labor

- retained products of conception

Physical Examination

- vaginal bleeding

- s/s of hypovolemia

Management

- IV fluids and blood products as needed

- tranexamic acid (to promote clotting)

- uterine atony: uterine massage; oxytocin 20- 40 IU/L 0.9% NaClIV; ergot derivatives (contraindicated for preeclampsia and hypertension); vasopressors

- trauma: surgery to repair cause of bleed

- retained tissue: manual removal of placental tissue

- coagulopathy: replace clotting factors (platelets and/or FFP)

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

Pathophysiology

Hyperemesis gravidarum is severe nausea and vomiting that occur during pregnancy. While there is no definitive diagnostic line between hyperemesis and common “morning sickness,” hyperemesis is generally defined as frequent vomiting that results in weight loss and ketonuria. Severe vomiting can lead to dehydration, hypovolemia, and electrolyte imbalances.

Hyperemesis usually presents around 6 weeks gestation and resolves around 16 to 20 weeks. However, for some women it may persist until delivery.

Risk Factors

- personal or family history of hyperemesis

- previous nausea and vomiting related to estrogen-based medications or

- motion sickness

- multifetal pregnancy

- young age

- hydatidiform mole

Physical Examination

- persistent vomiting (> 3 times per day)

- weight loss of > 5 pounds or > 5% of body weight

- s/s of hypovolemia

Diagnostic Tests

- elevated BUN

- elevated urine specific gravity

- serum electrolytes showing hypokalemia or other imbalances

- urinalysis positive for ketones

- elevated AST and ALT

Management

- IV fluids

- initial infusion of lactated Ringer's followed by dextrose

- urine output 100 ml/hour

- replace lost vitamins and minerals: IV thiamine, IV multivitamin, IV magnesium, calcium, or phosphorus as indicated by labs

- IV antiemetics

Neonatal Resuscitation

Pathophysiology

The transition to extrauterine life requires a complex series of changes in the cardiopulmonary system of a neonate. The alveoli in the neonate’s lungs expand, usually beginning with the first breath, and the lungs are cleared of fluid. In addition, the clamping of the umbilical cord combined with the expansion of the lungs raises the neonate’s blood pressure and pushes blood into the vasculature of the lungs.

A small number of neonates (around 10%) will require intervention to establish ventilation. Poor respiratory performance can have a number of causes:

- blocked airway

- lack of respiratory effort (usually the result of musculature or neurological deficits)

- persistent pulmonary hypertension in the newborn heart or lung defects

- preterm labor (lungs are not mature enough to clear and expand)

Physical Examination

- absence of spontaneous breath

- absence of vigorous cry

- airway obstruction (nares and/or trachea)

- cyanosis

- poor muscle tone

Management

- Stimulate the neonate by rubbing back, feet, and/or chest vigorously.

- Prevent heat loss by placing child in warmer,

- Clear airway of obstructions using bulb suction or wall suction (low suction).

- If stimulation and warming do not work, activate neonatal resuscitation code.

- Neonatal resuscitation is a specialized skill and requires supplemental education and certification. The ED nurse should be prepared to provide basic resuscitation of a neonate until the appropriate caregivers can arrive.

- Apply oxygen with positive pressure ventilation.

- If the neonate is apneic and the heart rate is < 60, initiate CPR.

- Goals of neonate resuscitation:

- spontaneous respiration

- heart rate > 100 bpm

- SpO2 85% to 95% by 10 minutes post delivery

Postpartum Infection

Pathophysiology

Postpartum patients are frequently discharged soon after delivery and may develop postpartum infections at home that require further treatment. Possible sites of infection include the endometrium (endometritis), surgical incisions, breasts (mastitis), and urinary tract. The infection may spread and lead to septicemia, peritonitis, or sepsis.

Risk Factors

- cesarean delivery

- vaginal infections

- manual rupture of membranes

Physical Examination

- fever of > 100.4°F (38°C):

- on more than 2 of the first 10 days postpartum

- maintained over 24 hours after the end of the first day postpartum

- endometritis: uterine tenderness, midline lower abdominal pain

- surgical incision infection: erythema and inflammation at incision, purulent exudate

- mastitis: erythema and tenderness in breast

Diagnostic Tests

labs show infection

Management

- endometritis and UTI: antibiotics, analgesics, antipyretics

- surgical incision: drain, irrigate, and debride wound

- mastitis: antibiotics, analgesics, antipyretics, empty breast of milk

Preeclampsia and Eclampsia

Pathophysiology

Preeclampsia is a syndrome caused by abnormalities in the placental vasculature. The syndrome is characterized by hypertension in the mother paired with either proteinuria or end-organ dysfunction. Symptoms can appear after the twentieth week of pregnancy and most commonly appear after 34 weeks.

In most cases, preeclampsia will resolve after delivery, but symptoms can develop postpartum. Maternal postpartum preeclampsia generally occurs within 6 days after childbirth but can be delayed up to 6 weeks after delivery. It can occur even if there was no evidence of preeclampsia prior to delivery. Because preeclampsia is usually diagnosed during routine prenatal care, postpartum preeclampsia most commonly presents in the ED.

Preeclampsia is classified as being either with or without severe features. Preeclampsia with severe features can lead to life-threatening complications, including eclampsia, pulmonary edema, and abruptio placentae.

Eclampsia is the onset of tonic-clonic seizuresin women with preeclampsia. Eclampsia can occur ante-, intra-, or postpartum. It is an emergent condition that requires immediate medical intervention.

Risk Factors

- age > 35

- personal or family history of preeclampsia

- obesity

- pregestational diabetes

- pregestational hypertension

- nulliparity or multifetal pregnancy

- chronic kidney disease

Physical Examination

- hypertension: systolic BP > 140 mmH? or diastolic BP > 90 mmHv

- facial edema

- rapid weight gain (> 5 pounds a week)

- severe preeclampsia: headache, epigastric pain, pitting edema

- eclampsia: tonic-clonic seizures

Diagnostic Tests

- proteinuria diagnosed through urine sample

- 24-hour urine protein: > 0.3 g

- urine dipstick protein: > 1+ (mild preeclampsia) to > 3+ (severe preeclampsia)

- serum creatinine: > 1.2 mg/dL indicates severe preeclampsia

Management

- definitive treatment: delivery of fetus

- management of symptoms

- antihypertensives (labetalol, hydralazine, or short-acting nifedipine)

- prophylactic magnesium (to prevent seizures)

- admit to OB

HELLP Syndrome

Pathophysiology

HELLP syndrome is currently believed to be a form of preeclampsia, although the relationship between the two disorders is controversial and not well understood. Around 85% of women diagnosed with HELLP will also present with symptoms of preeclampsia (hypertension and proteinuria). HELLP is characterized by:

- hemolysis (H)

- elevated liver enzymes (EL)

- low platelet count (LP)

Physical Examination

- hypertension: systolic > 140 mmHg or diastolic > 90 mmHg

- RUQ abdominal pain

- nausea and vomiting

- severe headache or visual disturbances

Diagnostic Tests

- urine protein consistent with preeclampsia diagnosis

- schistocytes on blood smear

- platelets: < 100,000 cells/pL

- total bilirubin: > 1.2 mg/dL

- AST: > 70 units/L

Management

- antihypertensives (labetalol, hydralazine, or short-acting nifedipine)

- prophylactic magnesium (to prevent seizures)

- admit to OB

Threatened/Spontaneous Abortion

Pathophysiology

Spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) is the loss of a pregnancy before the twentieth week of gestation. (Death of the fetus after the twentieth week is commonly referred to as a stillbirth.) Spontaneous abortions are a common complication of early pregnancy. They can occur because of chromosomal or congenital abnormalities, maternal infection or disorders, or trauma.

Spontaneous abortions are classified by the location of the embryo/fetus and cervical dilation.

- missed abortion: occurs when the embryo/fetus is nonviable but has not been passed from the uterus and the cervix is closed

- threatened abortion: occurs when the patient has vaginal bleeding before 20 weeks and the cervix is closed; may progress to incomplete or complete aBortion

- inevitable abortion: occurs when the patient has vaginal bleeding and the cervix is dilated but the embryo/fetus remains in the uterus; often accompanied by abdominal pain or cramps.

- incomplete abortion: occurs when the patient has vaginal bleeding, the cervix is dilated, and the embryo/fetus is found in the cervical canal

- complete abortion: occurs when the embryo/fetus has been completely expelled from the uterus and cervix and the cervix is closed

- septic abortion: occurs when the abortion is accompanied by uterine infection; it is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate medical intervention.

Risk Factors

- age > 35

- underweight or obese mother

- pregestational hypertension

- infection, particularly with fever

- endocrine disorders

- smoking

- cocaine or alcohol use

Physical Examination

- vaginal bleeding

- passage of fetal tissue

- radiating pelvic pain

- signs and symptoms of cessation of pregnancy (e.g., nausea, breast tenderness)

- s/s of infection with septic abortion

Diagnostic Tests

- fetal Doppler to assess for fetal cardiac activity

- transvaginal ultrasound to confirm pregnancy loss

Management

- RhoGAM if mother is Rh negative

- analgesics

- monitor patient for hemodynamic instability

- OB referral

- septic abortion: antibiotics and prep patient for surgery

Obstetrical Trauma

Pathophysiology

Trauma is the leading nonobstetric cause of death for pregnant people. Common causes of trauma include, falls, and intimate partner violence. Trauma is categorized as majority involves the abdomen, includes high force, or results in vaginal bleeding or decreased fetal movement. Minor trauma does not involve the abdomen and may include no obvious signs and symptoms.

However, minor trauma can still be fatal for mother or fetus, so a thorough assessment should be done on any trauma patient who may be pregnant.

In the ED, the patient should be assessed and stabilized before the fetus is assessed. Pregnant patients presenting to the ED should be evaluated for any non-pregnancy-related issues and then referred to OB if necessary.

Physical Examination

- visible signs and symptoms of injury, including ecchymosis and

- lacerations

- vaginal bleeding

- tense abdomen

- decreased uterine tone

- presence of amniotic fluid due to membrane rupture

Diagnostic Tests

- transvaginal ultrasound to assess fetus, locate placenta, and assess for abruption

- FAST ultrasound to assess for hemorrhage suspected

Management

- priority: assess mothers ABCs

- oxygen, respiratory intervention, or cardiac resuscitation as needed

- IV fluids or blood products as needed

- RhoGAM if mother is Rh negative

- betamethasone for imminent delivery of fetus < 34 weeks

- monitor fetal HR and uterine contractions

- OB consult for all obstetric trauma patients

Read More