Some Practice CEN Study Guide present ethical dilemmas, requiring students to analyze moral principles and make ethically responsible choices.

Ocular Emergencies CEN Study Guide

Abrasions

Pathophysiology

A corneal abrasion is a scratch or abrasive friction on the outer surface of the epithelium (the cornea's outer layer). Symptoms, severity, and outcome are variable based on the layers of the cornea involved and the size of the area affected. Corneal abrasions typically heal within 24 - 72 hours without complications, but in some cases may progress to infection, keratitis, or ulceration.

Corneal lacerations extend into the deeper layers of the cornea and are more symptomatic and painful than corneal abrasions. Lacerations are considered partial thickness (closed globe) and do not penetrate the globe structure of the eye.

Physical Examination

- Painful pressure or burning sensation.

- Sensation of foreign body or grit.

- Lacrimation or discharge.

- erythema or edema.

- Decrease in visual acuity: may be described as blurred, dull, or foggy.

Diagnostic Tests

- Fluorescein staining.

- Slit lamp or Woods lamp exam to identify the degree of injury or illness.

Management

Irrigate to remove foreign body, if present topical anesthetic, NSAIDs, and antibiotics ophthalmic lubricating solution lacerations may require surgery.

Burns

Pathophysiology

Ocular burns are classified as chemical (subdivided as alkali- or acid-based) or radiant energy (thermal or ultraviolet). Chemical burns occur through splash, spray, or direct touch. Alkali burns penetrate deep into the eye, causing liquefactive necrosis, while acidic burns cause coagulated necrosis closer to the surface of the injury. Radiant energy burns occur from exposure to intense heat, explosions, hot cooking oils, electrical arcs, lasers, and direct gaze into ultraviolet light.

The outcome varies based on the agent of exposure, time length of exposure, and ocular structures involved, but usually involves some degree of vision loss. Ocular burns tend to occur bilaterally and often in combination with other injuries such as dermal burns, penetrating objects, and compromised airways.

Physical Examination

- Extreme pain or burning sensation.

- Erythema and edema.

- Copious lacrimation.

- Decrease in visual acuity.

- History of chemical or radiant energy exposure.

Management

- Maintain airway and assess for concurrent injury.

- Irrigate for minimum of 30 minutes with isotonic solution.

- Assess pH level after irrigation; if > 7.4, continue with additional irrigation.

- Topical anesthetics may be added to irrigant solution.

- Morgan Lens: as needed assist with irrigation

- Topical corticosteroids, antibiotics, and cycloplegics.

- Occlusive dressing as needed

- Obtain chemical safety data sheet and consider consultation with regional poison control center.

Foreign Bodies

Pathophysiology

Ocular foreign bodies are any substance or object that does not belong in the eye. Size, shape, substance, impact velocity, and location will greatly impact severity of symptoms and ultimate outcome.

- Foreign bodies are described based upon their location.

- Extraocular (lid, sclera, conjunctiva, and cornea)

- Intraocular (anterior chamber, iris, lens, vitreous, retina, and intraorbital)

Physical Examination

- Visible foreign object.

- Sensation of foreign body or grit.

- Painful pressure or burning sensation.

- Penetrating injury: bleeding.

- Lacrimation or discharge.

- Erythema or edema.

- Blepharospasm

- Photosensitivity or decrease in visual acuity.

Diagnostic Tests

- Fluorescein staining

- Slit lamp or Woods lamp exam to identify the degree of injury or illness.

Management

- Irrigate with normal saline or eye wash solution.

- Evert upper lid to confirm absence/presence of a foreign body.

- Morgan Lens for extraocular foreign bodies, or if the sensation of a foreign body is present but the foreign body is not visible.

- Remove foreign body using a cotton-tipped applicator, metal spud, or 25-gauge needle (extraocular only).

- Topical anesthetic, NSAIDs, and antibiotics.

- Ophthalmic lubricating solution.

- Patch if a foreign body is retained (pending ophthalmology referral).

- Immediate ophthalmology referral for all intraocular foreign bodies.

Increased Intraocular Pressure

Pathophysiology

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases that cause an increase in intraocular pressure (IOP), resulting in compression of the optic nerve. The compression causes degeneration of the optic nerve fibers and apoptosis of the retinal ganglion cells, resulting in permanent vision loss.

Types of glaucoma include:

- Primary open-angle glaucoma.

- Normal tension (low-pressure) glaucoma.

- Secondary ’glaucoma related to diabetes or cataracts.

- Angle-closure glaucoma.

Most glaucomas are chronic and develop slowly and painlessly over time. The emergency nurse should be familiar With the visual impact of these chronic glaucomas, as the patient may have a deficit of peripheral vision that can impact communication methods.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma is a medical emergency that occurs when IOP increases rapidly to 30 mm Hg or higher (normal pressure is 8 - 21 mm Hg). Permanent vision loss from compression of the optic nerve can occur in as little as several hours if not rapidly treated. Additionally, scarring of the trabecular meshwork can lead to chronic forms of glaucoma, and cataracts can develop as latent complications. Acute onset commonly occurs in conjunction with pupil dilation, such as when transitioning from light to dark environments.

The information below relates to acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Risk Factors

- Family history

- Being of Asian descent

- More common in women

- Age > 60

- Hyperopic vision

- Shallow anterior chamber

- Thickened lens

Physical Examination

- Abrupt onset of pain

- Visual changes: described as blurry, cloudy, or halos of light.

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Erythema

Diagnostic Tests

- Corneal edema with clouding.

- Fixed pupil, mid-dilated (5-6 mm).

- Tono-Pen: increased intraocular pressure.

- Fundoscopic exam: pale, cupped optic disc.

- Slit lamp exam: shallow anterior chamber.

Management

- first-line pharmacological treatment:

- Topical miotic ophthalmic drops (pilocarpine).

- Topical beta-blockers (timolol)

- Topical alpha-adrenergic agents (apraclonidine)

- IV administration of acetazolamide or mannitol.

- Immediate ophthalmology referral and consult.

Ocular Infections

Conjunctivitis (pink eye) is the inflammation of the thin connective tissue that covers the outer surface of the sclera (bulbar conjunctiva) and lines the inner layers of the eyelids (palpebral conjunctiva).

- Diagnosis: burning or itching sensation; increased lacrimation (clear or yellow); erythema of sclera and inner eyelids; edema of palpebra; typically no decrease in visual acuity.

- Management: warm or cool compress for comfort; topical antibiotics if indicated; topical steroid if severe periorbital edema is present; ophthalmic lubricating solution.

Uveitis is the inflammation of any of the structures in the uvea, including the iris (iritis or anterior uveitis), the ciliary body (intermediate uveitis), or the choroid (choroiditis or posterior uveitis).

- Diagnosis: pain described as global aching or tenderness; ciliary spasm; conjunctival erythema; photophobia; vision changes; vitreous floaters; keratitis; Tono-Pen (increased intraocular pressure).

- Management: topical mydriatic ophthalmic drops to dilate the pupil; topical corticosteroids; referral to ophthalmology within 24 hours.

Retinal Artery Occlusion

Pathophysiology

Retinal artery occlusion (sometimes referred to as an ocular stroke) occurs when there is a blockage of vascular flow through the retinal arteries, resulting in a lack of oxygen delivery to the nerve cells in the retina. Blockage may occur from thrombi or emboli.

Risk Factors

- Heart or vascular disease

- Artificial heart valves

- A-fib

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Sickle cell disease

- Pregnancy

- Use of oral contraceptives

- Iv substance abuse

Physical Examination

Unilateral, sudden, painless loss of vision.

Diagnostic Tests

- Tono-Pen (increased intraocular pressure)

- Dilated fundoscopic exam

- Red fovea (cherry-red spot)

- Optic disc pallor and edema

Management

- Topical beta blockers

- IV acetazolamide

- IV mannitol

- IV methylprednisolone

- Ocular massage

- Immediate referral to ophthalmology

Retinal Detachment

Pathophysiology

Retinal detachment occurs when the pigmented epithelial layer of the retina separates from the choroid layer (visualize how thin layers of an onion peel can separate from each other) because of tension, trauma, or fluid accumulation between the layers. Vision loss results from lack of available oxygen and deterioration of photoreceptor cells.

Risk Factors

- Age > 65

- History of cataract surgery

- Trauma

- High myopia (nearsightedness)

- Diabetes

- Marfan’s syndrome

- Uveitis inflammation

- Hypertension

- Neovascular (“wet”) macular degeneration.

Physical Examination

- Painless onset of visual changes.

- Loss of vision is not immediate (unlike retinal artery occlusions).

- Reduction in peripheral vision and curtain-like shadow over visual field.

- Sudden or gradual increase of multiple floaters (wispy spider web-like formations that “float" across the visual field.

Diagnostic Findings

- Fundoscopic exam to assess for Schafer’s sign, vitreous hemorrhage, and scleral depression.

- Ocular ultrasound.

Management

- Stabilize patient and treat underlying injuries.

- Bedrest and quiet environment.

- Immediate referral to ophthalmology.

Ocular Trauma

GLOBE RUPTURE

Pathophysiology

A global rupture (open globe) occurs from a full-thickness laceration or tearing of the cornea and sclera. Rupture may occur as the result of blunt trauma, penetrating injury (entry wound without exit), or a perforating injury (entry and exit wounds present). Rupture can also occur post-trauma due to a rapid rise in intraocular pressure.

Physical Examination

- Eccentric or teardrop-shaped pupil.

- Sunken eye appearance and loss of volume a gross deformity or misshapen eye.

- Ocular pain.

- Subconjunctival hemorrhage.

- Decreased visual acuity.

- Edema, erythema, or ecchymosis.

- Tenting of the sclera or cornea at the site oi globe puncture.

Figure: Teardrop Pupil

Diagnostic Findings

- Seidel test positive (indicating leakage of aqueous humor)

Management

- Maintain bedrest; elevate head of bed 30 degrees.

- Manage IOP

- Shield both eyes (to prevent eye movement).

- Keep patient NPO and prep for surgery.

Do NOT:

- Irrigate

- Remove foreign body or penetrating objects.

- Measure intraocular pressure.

- Use pressure or absorbent dressings.

HYPHEMA

Pathophysiology

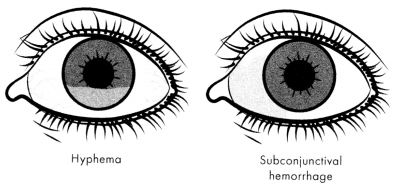

Hyphema is a collection of blood inside the anterior chamber between the cornea and iris. Blood accumulates as a result of a traumatic tear in the vascular structure of the iris or pupil, and it may rise to a level that fully occludes all vision.

Hyphema bleeding differs in appearance from bleeding that is seen with a subconjunctival hemorrhage. Hyphema is dependent; the blood rises in a horizontal fashion in front of the iris as it accumulates, similar to how water levels rise in a closed chamber.

Figure: Hyphema versus Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

A subconjunctival hemorrhage is painless and occurs from rupture of localized surface vessels in the sclera. A subconjunctival hemorrhage is irregularly shaped, covers the white portion of the eye, and does not result in visual deficit or loss.

Physical Examination

- Visible accumulation of blood.

- A decreased visual acuity.

- Pain and headache.

Management

- Maintain bedrest; elevate head of bed > 45 degrees

- Manage IOP

- Low-risk patients: rest and monitoring.

- High-risk patients: pharmacological management (topical corticosteroids, cycloplegics, beta-blockers, or alpha-adrenergic agents [clonidine]).

Ulcerations and Keratitis

Pathophysiology

Ulcerative keratitis is characterized by crescent-shaped inflammation of the epithelial layer that progresses to necrosis of the corneal stroma. Ulcers may occur from infectious or noninfectious causes, and they form scar tissue when healing. Without treatment, ulcers may infiltrate deeper structures of the eye, causing secondary uveitis, prolapse of the iris or ciliary body, hypopyon, and endophthalmitis/panophthalmitis.

Risk Factors

- Traumatic injury.

- Diabetes.

- Immunodeficiency.

- Systemic side effects of some medications (e.g., amiodarone, fluoro-quinilones, antimetabolites/neoplastic agents, tamoxifen, NSAIDs, thorazine).

- Side effects of topical medications (allergic ulcerative keratitis).

- Use of contact lenses.

Physical Examination

- Painful pressure, severe pain, or burning sensation.

- Increased lacrimation.

- Erythema and edema.

- White or cloudy spot on cornea a sensation of foreign body or grit.

- Decrease in visual acuity: may be described as blurred, dull, or foggy.

- Diagnostic Findings.

- Culture and sensitivity.

Management

Empiric administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics a warm compress and topical cycloplegics.

Read More