We are offering comprehensive collections of Practice CEN Study Guide to facilitate self-assessment and exam preparation.

Musculoskeletal Emergencies CEN Study Guide

Amputation

Pathophysiology

An amputation occurs when a body part is separated from the body by surgical or traumatic means. Traumatic amputations typically occur in the extremities and may include fingers, toes, hands, feet, arms, or legs. Amputations are categorized as complete or incomplete (partial).

- Complete amputations occur when the body part is entirely separated from the body.

- Incomplete or partial amputations occur when the body part is non-functional but still technically connected by a tendon, ligament, or other tissue.

Severe hemorrhaging may be absent in some amputations due to the tendency for severed blood vessels to spasm and retract. Partial amputations or those with significant tissue damage (such as crush injuries) will likely result in more blood loss than cleanly severed body parts.

Replantation (surgical reattachment of the amputated body part) may be considered based on the patient and type of injury. Indicators for a high chance of successful replantation include:

- pediatric patients

- patients with amputated digits, wrists, or forearms

- patients with sharp amputation (instead of blunt)

- <6 hours since amputation (longer for digits or for cooled tissue)

Management

- direct pressure and pressure dressing for bleeding

- IV fluids and blood products as needed

- preserve detached limb

- wrap in sterile gauze and moisten with normal saline

- place in tightly sealed bag and place bag on ice

- gently replace attached tissue and maintain normal positioning

- cleanse area with sterile saline solution and cover with thick material

- analgesics, antibiotics, and tetanus immunization as needed

Compartment Syndrome

Pathophysiology

Compartment syndrome is the result of increased intra-compartmental pressure, usually as a result of a fracture or crush injury. When the increased pressure in the closed compartment exceeds the pressure of perfusion, blood circulation is impaired, resulting in ischemia of the nerves and muscle tissue. Oxygen deficiency and the buildup of waste produce nerve irritation, resulting in pain and a decrease in sensation. With the progression of ischemia, muscles become necrotic, which can lead to rhabdomyolysis, hyperkalemia, and infection if left untreated.

Lower legs and arms are the most common areas; compartment syndrome can also occur in the abdomen.

Risk Factors

- extremity fractures (most common)

- crush injuries, severe contusions, or burns

- sepsis

- casting or compression bandage

- blood clots

- prolonged periods of unconsciousness

- after abdominal surgery or repair of vascular injury

Physical Examination

- the 5 P's

- pain (not proportional to injury and does not respond to opioid

- medications)

- paresthesia

- pallor

- paralysis

- pulselessness

- decreased urine output

- hypotension

- tissue tight on palpation

- edema with tight, shiny skin

Diagnostic Tests

- intra-compartmental pressure > 30 mm Hg

- delta pressure (DBP- compartment pressure) < 30 mm Hg

Treatment and Management

- remove casts or dressings to relieve pressure

- IV fluids: maintain urine output > 30 cc/hr

- intra-compartmental pressure >30 mm Hg: prepare patient for fasciotomy

- intra-compartmental pressure 10- 30 mm Hg: monitor pressure and hemodynamic status

- analgesics

Ligament Tendon Injuries

Pathophysiology

Sprains, strains, and rupture are very common injuries and share similar signs and symptoms.

- Sprains are the tearing or stretching of ligaments.

- Strains are the separation of muscle or tendon from bone.

- A rupture occurs when a tendon is torn or separates from muscle. Common locations of tendon ruptures include the Achilles tendon, the bicep tendons, and the patellar tendon.

Risk Factors

- overextension with severe stress applied (e.g., pivoting on knee, falling on wrist)

- falling

- throwing objects when running or jumping

- heavy lifting

- awkward position when lifting

Physical Examination

- localized pain and edema

- decreased ROM

- hear or feel a pop on incident

Diagnostic Tests

X-ray to rule out fracture

Management

- mild sprains or strains typically treated at home

- RICE: rest, ice, compression, and elevation

- analgesics as needed

- immobilization for severe injury

Fractures

Pathophysiology

A fracture is any break in a bone. Open fractures include a break in the skin; with a closed fracture, the skin is intact. Fractures to the hand, wrist, arm, lower leg, foot; and ankle can often be managed in an acute care setting with reduction and splinting/casting. Complications such as hemorrhage, neurological damage, or compartment syndrome may require additional consultations or hospital admission.

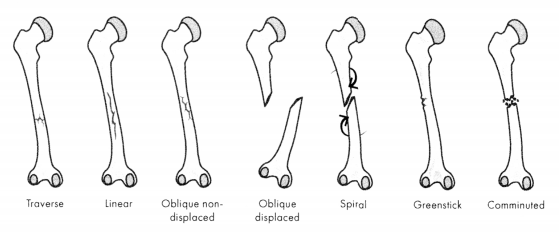

Further classifications of fractures are made based on the configuration of the fracture.

- Non-displaced: Broken area ofthe bone remains in alignment; this is the optimal condition for reduction and healing.

- Displaced: Broken areas ofbone are not aligned.It may require manual or surgical reduction including hardware for fixation.

- Transverse: A horizontal breakin a straight line across the bone occurs from a force perpendicular to the break.

- Oblique: A diagonal break occurs from a force higher or lower than the break.

- Spiral: A torsion or twisting break around the circumference of the bone is common in sports injuries.

- Comminuted: The break is fragmented into 3 or more pieces. This is more common in people older than 65 and those with brittle bones.

- Compression: The break is crushed or compressed, creating a wide, flattened appearance.It frequently occurs with crush injuries.

- Segmental: Two or more areas of the bone are fractured, creating a segmented area of"floating" bone.

- Greenstick: In this type of incomplete break, the bone is not completely separated and bends to one side; it is common in children.

- Avulsed: A “chip” fracture displaces small segments of bone from the main bone at the area of tendon/ligament attachment. It results from tension/pulling of the tendons/ligaments away from the bone.

- Torus/buckle fracture: This is an incomplete fracture with bulging of the cortex, common in children.

- Impacted: The ends of the bone are impacted or “jammed” into each other from forceful impact.

- Salter-Harris: This is a growth plate fracture, classified as I- V

Figure 14.1. Types of Fractures

Fractures of the pelvis or femur require complex stabilization and place patients at high risk of complications, including internal hemorrhage, organ perforation, hematoma formation, and lipid embolisms.

Fat embolism syndrome (FES) is caused by fat in the pulmonary circulatory system and can occur after long bone or pelvic fractures. A cardinal cutaneous sign of emboli is reddish-brown non-palpable petechiae that appear over the upper body (particularly in the axilla region) 24- 36 hours after the trauma event Other symptoms include hypoxemia, dyspnea, altered mental status/ decreased LOC, and fever.

Physical Examination

- pain and tenderness increasing with movement

- swelling

- visual or palpated deformity

- crepitus

- abnormal movement or decreased ROM

- inability to bear weight

- contusions or bleeding

Diagnostic Tests

X-ray

Management

- analgesics

- cleanse open wounds and cover with sterile dressing

- reduce (manual or surgical as indicated)

- immobilize

- stabilize at the joints above and below the injury

- position the splinted limb as close to anatomically normal as possible

- do not reposition the limb if there is resistance or evidence of further injury

- reassess pulses, motor function, and sensation after the splint is in place

- pelvic or femur fracture:

- pelvic binder/traction splint

- be prepared to administer blood products as needed

- IV fluids and respirator support for FES

Dislocations

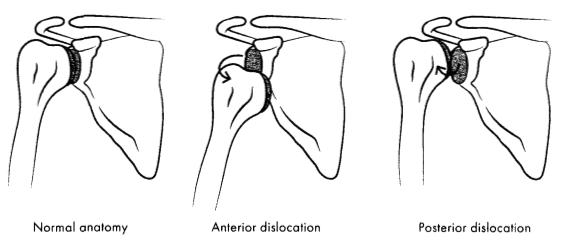

Pathophysiology

Dislocations involve bones being separated or “disrupted” from the joint they are a part of. Most dislocations are caused by sudden, abnormal force placed on the joint. Common causes of dislocations include falls, motor vehicle collisions, and athletics; common sites include shoulders, fingers, hips, and knees.

Figure 14.2. Shoulder Dislocation

Dislocations usually result in damage to ligaments and tendons and may damage muscles and blood vessels. Significant damage may still have occurred even if the joint was restored (sometimes done by the patient or bystanders).

Physical Examination

- intense, localized pain at the joint

- deformity of joint

- loss of function or range of motion

- absent pulses distal to injury (with blood vessel damage or constriction)

Diagnostic Tests

X-ray

Management

- assess distal pulses, motor function, and sensation

- reduce as splint as soon as possible to prevent neurovascular injury

Inflammatory Conditions

ARTHRITIS

Pathophysiology

Arthritis is inflammation in the joints caused by autoimmune conditions or the accumulation of chemical byproducts in the connective tissues. Inflammation causes a thickening of the synovial membrane and leads to irreversible damage to the joint capsule and cartilage from scarring. Both acute and chronic conditions result in pain, erythema, swelling, and stiffness.

Common types of arthritis include:

- rheumatoid arthritis: progressive, symmetric inflammation of joints (most common in hands)

- psoriatic arthritis: arthritis accompanied by psoriasis

- osteoarthritis: progressive, usually presents in one to a few joints (most common form of arthritis)

- ankylosing spondylitis: arthritis of the spine

- gout: arthritis caused by buildup of uric acid in joints

Physical Examination

- erythema

- pain, edema, stiffness, deformity, and loss of function in joints

- fever or chills

- muscle pain and stiffness

Management

- treatment based on disease type, age, health, history, and severity of disease

- treat underlying disease

- topical or oral analgesics (NSAIDs)

- corticosteroids

Costochondritis

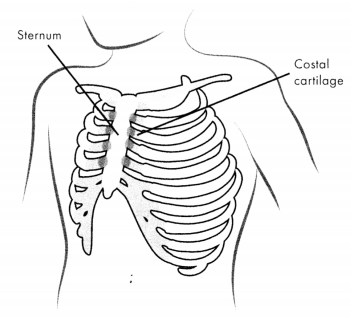

Pathophysiology

Costochondritis is the inflammation of the costal cartilage, which joins the ribs to the sternum. It usually affects the fourth, fifth, and sixth ribs. The inflammation causes the chest wall to be tender and painful upon palpation. There is no known definite cause, and the condition will generally resolve without treatment.

Figure 14.3. Costochondritis

Physical Examination

- sharp pain at chest wall; radiating to abdomen or back

- tenderness on palpation ofrib joints

- rib pain increases with deep breathing and movement of the trunk

- can cause dyspnea or anxiety

Management

- application of heat or ice

- anti-inflammatories

- steroid injection with local anestheticifanti-inflammatory is ineffective

- rest and avoidance of sports and exercise

Osteomyelitis

Pathophysiology

Osteomyelitis is an infection in the bone that can occur directly (after a traumatic bone injury) or indirectly (via the vascular system or other infected tissues).In children, osteomyelitis is most commonly found in the long bones of the upper and lower extremities, while in adults it is most common in the spine.

Physical Examination

- may be asymptomatic

- fever or chills

- pain at the site of infection

- s/s of local infection (warmth, exudate)

Diagnostic Tests

- MRI or CT scan

- positive blood culture or culture of bone biopsy

Treatment and Management

- surgical debridement

- IV antibiotics

Read More