Practicing with a variety of CEN Study Guide exposes students to different question formats, such as multiple-choice and select-all-that-apply.

Maxillofacial Emergencies CEN Study Guide

Abscess (e.g.. peritonsillar, dental)

Peritonsillar abscess/quinsy

Cause

Peritonsillar abscess is commonly referred to as quinsy, which usually results from bacterial infections that target the pharynx and the surrounding soft tissues. The causative agents include bacteria such as Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, and Bacteroides.

Clinical features

The symptoms include dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), sore throat, trismus Cocked jaw), hot potato voice, fever, ear pain and adenopathy (swollen lymph nodes). Patients may exhibit an unwell appearance, drooling, halitosis (bad breath) and tonsillar erythema (redness of the tonsils).

Treatment.

- Perform an incision and drain the abscess under local anesthesia.

- Use systemic antibiotics and supportive management: IV fluids, analgesia and antipyretics.

- Perform elective tonsillectomy for patients with recurrent tonsillitis and obstructive sleep apnea.

Parapharyngeal abscess

Cause

A parapharyngeal abscess is a collection of pus in the parapharyngeal space, which is located lateral to the pharyngeal constrictor muscle and medial to the pterygoid muscle. The common agents include Streptococcus, Staphylococcus and Bacteroides.

Clinical features

The manifestations include fever, odynophagia, sore throat and the swelling of the neck. Anterior space abscesses cause induration, trismus and tonsil bulging. Posterior space abscesses can cause pharyngeal wall swelling, high grade fever, neurologic deficits and sepsis.

Treatment

- Ensure proper airway management.

- Perform an incision and drain the abscess under local anesthesia.

- Perform empirical antibiotic therapy with parenteral antibiotics such as clindamycin and ceftriaxone.

Dental conditions (Dental caries)

Causes

Dental caries result from bacterial action in dental plaques. The risk factors include:

- Diets that are high in carbohydrates and sugars.

- The presence of dental plaque and dental defects such as fissures, grooves and enamel pits that reach the dentin.

- Reduced salivary secretion due to drugs, radiation exposure and systemic disorders.

- A low-fluoride and high-acid environment that results from soft drinks and energy drinks.

Clinical features

Dental caries can be asymptomatic if they affect only the enamel. If the dentin is affected, symptoms may include dental pain and tooth sensitivity.

Treatment

The treatment options include restorative therapy, root canal treatment and crown placement as needed.

Risk Factors

- Most common in teenagers and young adults ages 20 - 40

- Acute tonsillitis

- Smoking

- Poor oral hygiene

Physical Examination

- Visible abscess on soft palate

- Severe sore throat

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Fever

- Trismus

- Drooling

- Dysphagia

- Halitosis

Management

- Maintain airway.

- Analgesics, antibiotics, and/or corticosteroids.

- Incision and drainage or needle aspiration.

Epistaxis

Pathophysiology

Epistaxis is hemorrhage or bleeding in the nasal passages caused by rupture of vasodilated vessels in the mucous membranes. Rupture can occur in one or more vessels and more commonly presents unilaterally. Emergency treatment should be considered if bleeding cannot be self-controlled or compromises the airway.

Epistaxis may originate anteriorly or posteriorly. Anterior bleeding compromises the majority of epistaxis cases and is usually self-limiting. Posterior bleeding is less common but requires more aggressive treatment. Risk factors for posterior bleeding include hypertension, use of anticoagulants, and recent nasal surgery.

Physical Examination

- Visible frank bleeding from nares.

- Nasal speculum used to visualize source of bleeding.

Diagnostic Tests

Facial X-ray for injury

Management

- Manage airway

- Position patient sitting upright and leaning forward to prevent aspiration

- Anterior epistaxis

- Continuous pressure to midline septum by pinching with fingers for up to 15 minutes

- Nasal decongestant spray (oxymetazoline) for vasoconstriction

- Electrical or chemical (silver nitrate) cautery

- Nasal packing if bleeding continues

- Posterior epistaxis

- Nasal packing (balloon catheter)

- Hospital admission

Facial Nerve Disorders

BELL'S PALSY

Pathophysiology

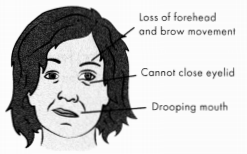

Bell's palsy is a unilateral facial paralysis or weakness caused by inflammation ’ of the facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve). Onset is sudden and facial droop is similar in appearance to droop present with a cerebrovascular accident. In most cases the weakness will resolve over weeks to months; occasionally, it may recur. Bell's palsy typically occurs in younger adults and children. Cause is unknown but may be related to viral infections, autoimmune disease, or vascular ischemia.

Risk Factors

- Pregnancy

- Diabetes

- Viral infection (herpes simplex virus, herpes zoster, flu)

Physical Examination

- Mild to total unilateral paralysis of facial muscles

- Characteristic facial droop painful sensations on

- Affected side difficulty speaking dysphagia

Figure: Bell's Palsy

Management

- Initial diagnostics to rule out CVA

- Corticosteroids

- Antivirals if indicated

- Patch on affected eye if diminished blink reflex to limit risk for corneal abrasion

- Oral glycerin swabs for dry mouth

- Yankauer suction for excess saliva

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA

Pathophysiology

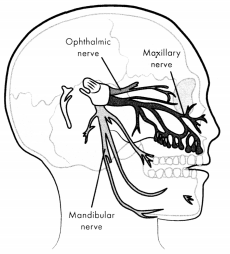

Trigeminal neuralgia—or ric douloureux—is a condition of the trigeminal nerve (fifth cranial nerve) that causes unilateral stabbing, shooting pain and burning sensations along the nerve branches. Paroxysms can affect any or all of the three nerve branches: ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular. The cause is unknown, but pressure and compression of the vascular vessels near the trigeminal nerve root is suspected.

Figure: The Trigeminal Nerve

Trigeminal neuralgia is chronic, and the slightest touch or stimulation may precipitate a painful episode. Painful spasms both start and end abruptly. The initial attacks may be short however, it can progress to longer and more frequent attacks.

Risk Factors

- Age-related anatomical changes of the cerebral artery and veins: most common in ages 50 - 60.

- More common in women

- Multiple sclerosis

- Facial trauma

Physical Examination

- Characteristic unilateral vain alon$ branches of the fifth cranial nerve.

- Abrupt onset and ending of pain lasting several minutes to several days.

- Facial muscle contractions causing eye to close and mouth to twitch on affected side.

Diagnostic Tests

MRI or CT to rule out neurovascular injury or lesion.

Treatment and Management

- Initial diagnostics to rule out CVA.

- First-line medications: carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine.

- Second-line medications: gabapentin, lamotrigine, baclofen.

- Surgical decompression if pain does not respond to medications.

Maxillofacial Infections

Acute otitis media is inflammation of the middle ear that usually results from inflammation in the mucous membranes. It is one of the most common reasons for ED visits in children.

- Diagnosis: otalgia; otorrhea; tugging on ear; perforated, opaque, bulging, or erythematous tympanic membrane.

- Management: usually heals spontaneously; oral antibiotics if membrane is intact; antibiotic drops in affected ear if membrane is ruptured; analgesics.

Ludwig's angina is a gangrenous cellulitis in the soft tissue of the neck and the floor of the mouth, generally following dental abscess. Edema in the neck and mouth places the patient at high risk for airway obstruction.

- Diagnosis: tongue enlargement and protrusion; sublingual pain and tenderness; compromised breathing; difficulty swallowing; drooling; labs and s/s consistent with infection.

- Management: manage airway; IV antibiotics; incision and drainage.

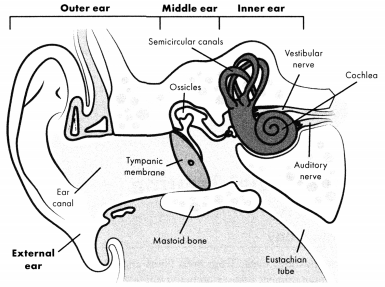

Mastoiditis is a bacterial infection of the mastoid air cells within the mastoid bone. It typically occurs secondary to acute otitis media.

- Diagnosis: otitis media; tympanic membrane rupture; papilledema; erythema and edema over mastoid process.

- Management: antibiotics; analgesics.

Sinusitis is inflammation and edema of the membranes lining the sinus cavities.

- Diagnosis: facial pressure and pain; headache; nasal congestion and blockage; green or yellow nasal discharge.

- Management: decongestant antihistamine; analgesics; antibiotics; corticosteroids; humidified air, warm compress, or saline nasal drops.

Acute Vestibular Dysfunction

LABYRINTHITIS

Pathophysiology

Labyrinthitis occurs in the inner ear when the vestibulocochlear nerve (eighth cranial nerve) becomes inflamed as the result of either bacterial or viral infection. The inflammation affects hearing, balance, and spatial navigation. Onset is characterized as acute, sudden, and painless. The initial episode is most severe, with subsequent episodes showing less intensity. Labyrinthitis symptoms can extend from several weeks to several months.

Physical Examination

- Dizziness and vertigo

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of balance

- Tinnitus or hearing loss

Diagnostic Tests

Imaging/labs to rule out neurological condition, Meniere’s disease.

Management

- Antibiotics or antivirals

- Corticosteroids

- Supportive care for symptoms: antihistamines, antiemetics, benzodiazepines.

MENIERE'S DISEASE

Pathophysiology

Meniere‘s disease is the result of chronic excess fluid in the inner ear. Fluid accumulation is the result of malabsorption in the endolymphatic sac or blockage of the endolymphatic duct. The excess fluid causes the endolymphatic space to enlarge, increasing inner ear pressure and possibly rupturing the inner membrane (not to be confused with rupture of the tympanic membrane in the middle ear as seen with otitis media).

While typically only one ear is affected, it does occur bilaterally in about 20% of cases. Onset may be minor with subtle symptoms, with subsequent episodes manifesting with more severe symptoms. Attacks can occur frequently, up to several times per week, or infrequently, several months or years apart. Attacks typically last anywhere from 20 minutes to 24 hours.

Figure: Anatomy of the Ear

Physical Examination

- Classic triad of symptoms: fluctuations in hearing/hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo.

- Pre-attack (aura): loss of balance, dizziness, pressure in ear, hearing loss or tinnitus, headache.

- mid-attack: sudden severe vertigo, anxiety, GI symptoms, blurred vision, nystagmus, palpitations.

- Post-attack: extreme exhaustion and need for sleep.

- Late-stage disease: permanent hearing loss and increases in balance/ visual disturbances.

Diagnostic Tests

Imaging/labs to rule out neurological condition, labyrinthitis.

Management

- Intratympanic gentamicin and steroids (injected by ENT).

- Diuretics (non-potassium-sparing) and reduced sodium diet.

- Supportive care for symptoms: antihistamines, antiemetics, benzodiazepines.

Maxillofacial Trauma

MAXILLOFACIAL FRACTURES

Pathophysiology

Maxillofacial fractures occur from both blunt and penetrating traumas. Emergency management focuses on maintaining a patent airway and stabilizing the patient for surgical intervention. Most fractures will involve the integrity of surrounding tissues, requiring complex repair to muscular, vascular, and dermal structures as well as the reduction and fixation of the affected bone.

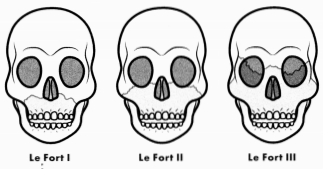

Types of maxillofacial fractures:

- nasal: most common of all facial fractures and least likely to need specialist consultation.

- orbital rim and blowout fractures: fractures of orbital floor or lateral and medial orbital walls; occur from direct blow to the orbit such as from a baseball or fist.

- mandibular: fractures of the lower jaw; may be singular or multiple.

- maxillary: fractures of the upper jaw.

- Le Fort I: horizontal fracture; separates teeth from upper structures—"floating palate”.

- Le Fort II: pyramidal fracture; teeth are the base of the pyramid, fracture passes diagonally along the lateral wall of the maxillary sinuses, apex of pyramid is the nasofrontal junction—“floating maxilla”.

- Le Fort III: craniofacial disjunction transverse fracture line passes through the nasofrontal junction, maxillofrontal suture, orbital wall, zygomatic arch, and zygomaticofrontal suture—"floating face".

Figure: Types of Maxillary Fractures

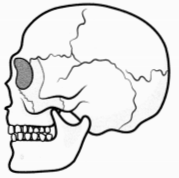

Zygomaticomaxillary complex (tripod) fracture: simultaneous fracture of the lateral and inferior orbital rim, the zygomatic arch, and lateral maxillary sinus wall; occurs from direct blow to the lateral cheek.

Figure: Zygomaticomaxillary Complex (Tripod) Fracture

PhysicalExamination

- Visible facial injury or deformity.

- Pain, tenderness, or paresthesia over the affected area.

- Epistaxis

- Ecchymosis

- Ocular: diplopia, restricted extraocular movements, decreased vision, enophthalmos, periorbital hematoma or edema, subconjunctival hemorrhage.

- Dental/oral: visible dental fractures or avulsions, impaired mastication, malocclusion, trismus, rhinorrhea of cerebrospinal fluid.

Diagnostic Tests

Facial X-ray or CT scan (head and neck)

Management

- Maintain airway.

- Cervical spine precautions.

- Treatment based on type and severity of injury.

- Goal of all treatments is to preserve function and minimize disfigurement.

SOFT TISSUE INJURIES

Pathophysiology

Penetrative and blunt trauma injuries to the maxillofacial region will cause soft tissue injuries that may obstruct the airway.

Physical Examination

- Visible entry wound or foreign object

- Bleeding

- Contusions, hematoma, or tissue edema

- Nasal drainage (rule out cerebrospinal fluid)

Management

- Priority: maintain airway

- Immobilize spine and neck as warranted.

- IV fluids as needed for hemorrhage.

- Apply direct pressure for hemorrhage.

- Clean or irrigate wounds, then dress.

- Analgesics

- Remove foreign object(s) when it is safe to do so; surgery to remove objects may be required.

Read More